FIRST PROJECT: 3 IMAGES

SECOND PROJECT: MAPPING

SECOND PROJECT: MAPPING My goal for this project was to map the disconcertment which accompanies the mediated image. To me, the mediated image is a specific moment, which, when captured and frozen, becomes a kind of non-representational reality. The problem that the mediated image poses rests in its tendency to obscure itself. Even though the formal image is necessarily a faithful representation of the reality which it freezes, the content of the image attempts to negate this represented truth. In this sense, the mediated image employs its content to undermine its materiality.

In this selection of three photographs, I chose to illustrate my conception of the mediated image in three staged scenes. The photo on the left shows a rabbit behind a rabbit mask. I hoped that this image might provide an introduction to the mapped theme in its portrayal of a clearly manipulated reality that does not seem formally imaginary or fantastic. The rabbit and the rabbit mask are really there; the captured moment is not retroactively transposed. However, there is something missing: the mediatory presence (the disembodied hand) shields the truth. The viewer is forced to ask him/herself whether the image tells a real or fabricated story. The middle image functions as a more literal example of the mediated image. Words are hidden from the viewer and the captured instant is not complete. The last image attempts to bring closure to the map. It hearkens back to the first image in its content, while at the same time proposing a migration of the mediated image from the private to public sphere. With the last image, I wanted to explore the possibility of the mediated image’s insertion into the everyday—in this case, a regulated image in a supermarket.

A disturbing contradiction lies in the fact that while a photograph is necessarily faithful to the moment which it captures, the mediated or regulated image interferes with the very premise of its existence. How can a specific moment exist when it is self-deceiving and therefore shirks its own duty to be real?

THIRD PROJECT: EMULATION (Robert Adams) When I first saw Robert Adams’ work, I remember a strange feeling of aesthetic self-affirmation that came over me. I was moved by Adams’ understated but powerful challenge to the dominant landscape aesthetic. It was now “permissible” that I bask in the toxic crabgrass of highway median, even that I might make art from my new realization. Adams’ photos helped me to see the import of non-spaces: forgotten swaths of earth which lie in a cultural and aesthetic purgatory. For Adams and his critics, these non-spaces—in real and replicated states—illuminate a number of contradictions that we are forced to deal with as artists and as regular human beings. Adams was concerned with reconciling the beauty and degradation contained in some of his images: “I loved some of the pictures, but I also knew I hated the places themselves, and had been unable to record convincingly what was wrong with them.” For me, Adams’ confusion appeared to center on a sense of humanistic irresponsibility that he felt while engaging in art-making. Concerned as he was with the human encroachment on the purity of Nature, Adams was not completely comfortable with the fact that this encroachment may result in photographic beauty.

In my emulation project I focused on two of the chain of opposing dualisms raised by Adams’ work. First of all, I hoped to examine empty, meaningless spaces circumscribed by defined, archetypal spaces and search for an illuminating tension between the two. Secondly, I hoped to focus on what I saw as Adams’ query into the naturalness of human destruction. As a guiding inspiration, I considered John Szarkowski’s opinion that Adams has “discovered in these dumb and artless agglomerations of boring buildings the suggestion of redeeming virtue. He has made them look not beautiful but important…in an unsparing way, natural.” In my image with the truck and my image of some buildings, I sought to reassert the existence of forgotten spaces in the face of other culturally prioritized spaces. In my photograph of the pond, I sought to extract one uninteresting, meaningless image from an infinity of boring, meaningless images in order to prioritize the non-space—the space that has no history, culture, or reference. In this way, I hoped to problematize the traditional mode of freezing certain, “interesting, special, and different” images over capturing one arbitrary image in a series of sameness and boringness. Formally, I attempted to recreate Adams’ usage of expansive but inactive skies and roads. Overall, I hoped to celebrate wo/man’s status in Nature as a “reshaper” and remove the inextricable bond between material and spiritual destruction.

Robert Adams, Beauty in Photography: Essays in Defense of Traditional Values, p. 66. Szarkowski, intro to Robert Adams, The New West: Landscapes Along the Colorado Front Range, p. x.

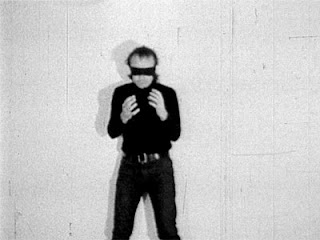

FOURTH PROJECT: PERSONA

For my project, I sought to focus on the identity of the forced persona. I was influenced by the notorious Abu Ghraib images that surfaced online to study both the persona of the torture victim and the way in which the meaning of non-art amateur images is changed when it is swallowed up by the media industry. In my photographs I first tried to address the way in which the victimized persona is aestheticized and turned to specatacle. I believe that the famous Abu Ghraib photos were not only popular because they were a political and moral outrage, but also beacause they were nice to look at. I think that part of this spectacle resides in the almost tangible power dyamic that exists between the torture victim and the torturer. he image becomes circus-like because the ivictim is humilated in such a way that s/he has no control over his/her own body. Another aspect of the spectacle resides in the erotic nature of torture photos. I was always fascinated that a woman was chosen to pose with the degraded corpses of male torture victims. In my project I tried to create some kind of accidental homo-eroticism in order to highlight the spectacle.

For the second aspect of my piece, I wanted to look at the ways in which amateur personal digital images become a kind of artistic practice when they are so drastically recontextualized. I put my images through a number of different media changes to try to recreate this cultural appropriation of the individual snapshot. The "torture scene" was originally videotaped, I took stills from the movie, I photoshopped these images and the used the machine in the slide library to transfer the digitial images onto negative. I think that both the quality and meaning of the photos change when they are subjected to a process like this. The non-intentional compositional practices of the original photographer are forced into an artistic context because the images do provoke an aesthetic response when they are so widely disseminated online. Overall, i find it interesteing how one image representing a persona that someone has no control over can become the persona of an entire group of people.

.jpg)